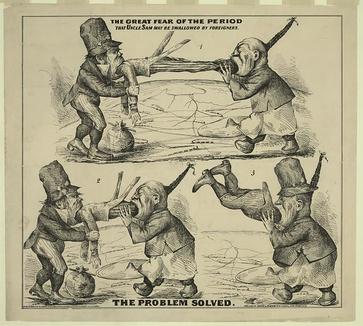

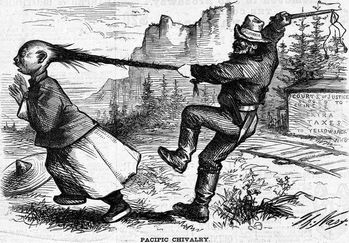

Many Americans did not tolerate the striking cultural differences of the Chinese and believed the immigrants could not assimilate. This created a sense of nativism and racial superiority that fueled more conflict about the presence of the Chinese.

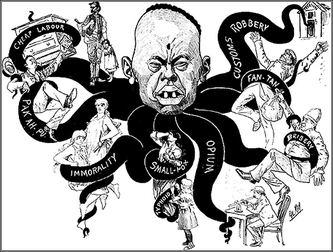

Offensive, exaggerated stereotypes against the Chinese alienated them from the American public.

"Many whites began to perceive the Chinese as criminals, partly because of a rise in Chinese prostitutes, cheap labor, and opium. They were seen as backwards, dirty, and reckless."

-Kevin Johnson (The History of Racial Exclusion in the U.S. Immigration Laws)

-Kevin Johnson (The History of Racial Exclusion in the U.S. Immigration Laws)

|

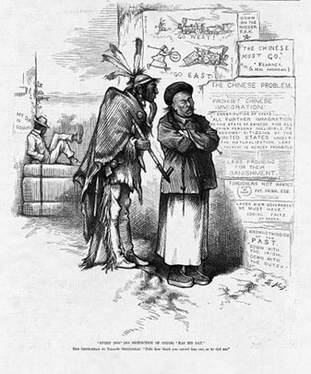

"Unlike European immigrants, the Chinese are not free and independent men... They should not be allowed to supersede the Caucasian race... We are confronted by the fact that the introduction into our country of an inferior race of men, who are immoral... operates as a displacement of the natives of the soil, and substitutes a non-assimilative alien, utterly unfit for and incapable of self-government."

-Senator John Miller, 1882 ("An Earnest Appeal to Congress") |

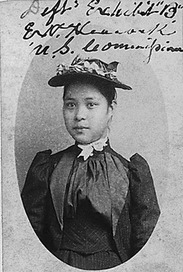

These beliefs resulted in the Page Law of 1875, which forbade "undesirable" immigration from Asia for "lewd and immoral purposes." The definition of "undesirables" targeted stereotypes and included any individual from Asia that was a forced laborer, a prostitute, or a convict.

"We must end the danger of immoral Chinese women."

-Representative Horace F. Page, 1875 ("Page Law")

-Representative Horace F. Page, 1875 ("Page Law")

New legislation was passed to harass Chinese customs and hinder immigrants' everyday lives.

|

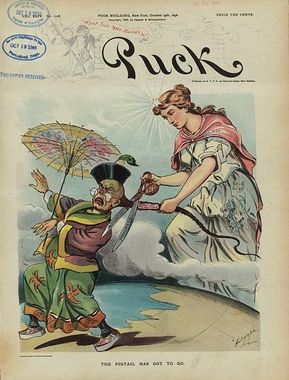

The Pigtail Ordinance forced San Francisco prisoners to have their hair cut within an inch of the scalp. This purposely outlawed the wearing of long braids by men, a Chinese style, and was ultimately repealed.

"The sheriff had cut my hair so maliciously... The ponytails worn by the Chinese were symbols of identity. The loss of one’s queue was considered a mark of disgrace and indicated suffering after death." -Ho Ah Kow, 1878 ("Petition Against the Pigtail Ordinance") |

|

The Sidewalk Ordinance banned the Chinese method of carrying goods on a pole, while the Laundry Ordinance of 1873 made it illegal to operate a laundry service without a permit.

"The Laundry Ordinance was passed in mind that two-thirds of laundries were owned by Chinese immigrants. After requiring that all laundries obtain licenses, San Francisco refused to issue them to the Chinese on the basis of their race." -Professor Madeline Hsu (Student interview) Yick Wo, a Chinese laundryman, sued against this ordinance in Yick Wo v. Hopkins, in which the Supreme Court established that laws could not be enforced in a discriminatory manner. |

Other Chinese also voiced opposition to discrimination, although they did not sway negative perceptions.

|

“The treatment of the Chinese in this country is all wrong and mean. There is no reason for the prejudice against the Chinese. There are few Chinamen in jails and none in the poor-houses. There are no Chinese tramps or drunkards. Many Chinese here have become sincere Christians, in spite of the persecution which they have to endure from their heathen countrymen.”

-Lee Chew, 1903 (The Biography of a Chinaman) |